How we talk about innovation motivated by the desire to do something about the impacts of human activity on the planet presents something of a conundrum. Search the popular press and media and you’ll find much discussion of “greenwashing” – exploiting the grey areas (ironically enough!) of product claims using vaguely defined terms to mislead eco-conscious but not necessarily fully-informed consumers.1, 2 Conversely, consumers can display paradoxical behaviour where their choices don’t back up the values they claim to espouse.3 When, for example, did you last turn down a coffee because it came in a disposal cup?

If we can’t trust the marketers or ourselves to do the right things, then who or what can we trust? They may be one or two stages removed from the consumer, or in the context of ETERNAL medical practitioners and patients, but in the view of Britest Technical Services Director Rob Peeling, “The scientists and engineers involved in creatively responding to the need to redesign manufacturing processes and product value chains for sustainability have an ethical duty to think deeply and holistically at a systems level about the change of which they conceive, and to determine as rigorously as possible that they are moving in the right direction.”4

This is not at all a straightforward matter. It can be challenging for innovators (not to mention customers and regulators) to get their heads around the complexities of things like Life Cycle Analysis and multiple environmental impact categories and just as tricky for specialists in environmental and ecotoxicity assessment methods to understand what the implications of changes to commercial processes and products might be on emissions to land, air or water. On top of this almost invariably, there will be considerable uncertainty about a new process design and any data about its performance, especially early in the development cycle, when the opportunity to avoid costly or reputationally damaging consequences of a bad outcome are at their greatest. Britest’s methodological development effort in ETERNAL is variously focused on helping innovators to find the most sustainable process route when faced with multiple possibilities, to identify and challenge the environmental impacts of the process, and to develop cost effective carbon footprint reduction plans across their products’ value chain from the earliest stages of the development lifecycle.

According to Rob Peeling, “The use of ‘green’ language has a valid part to play in transforming thinking and behaviour, but there is a risk that narrow or superficial understanding of the risks and benefits of innovation can lead to bad decision making and bad results without anyone intentionally trying to mislead. For me, the first step in any innovation project is to establish as clearly as possible a shared understanding of what are the drivers, objectives, and goals: why do things need to change, what change are we after, and how will we know if we’ve been successful?”

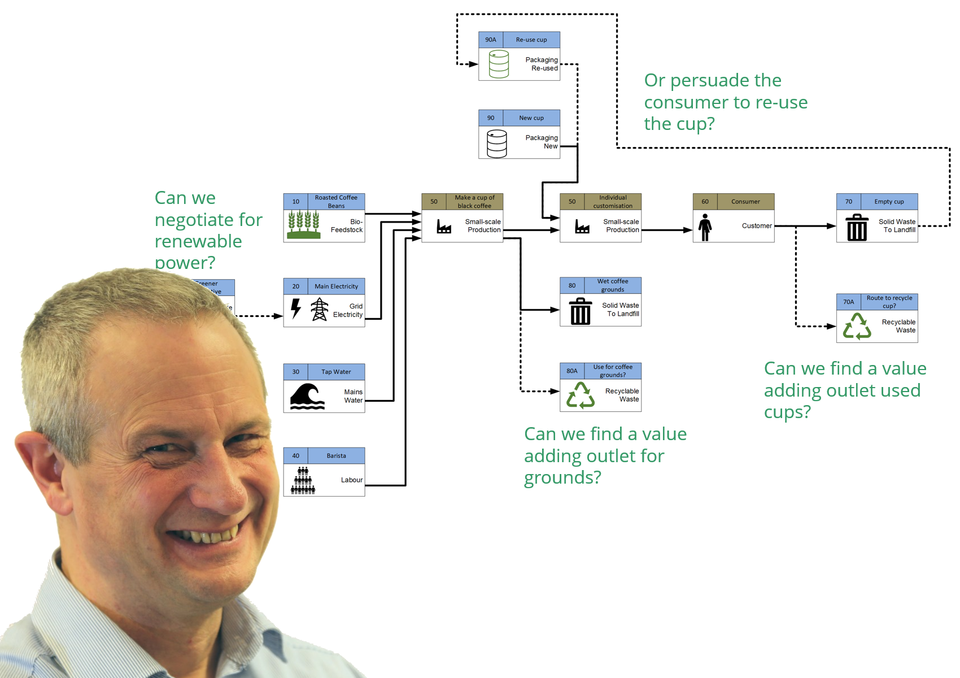

After that, the next priority is to develop a clear and comprehensive conceptual description of the new or improved process as a foundation for more detailed analysis. “Crucially, what we call a ‘Process Definition Diagram’ (PDD) provides a scale and equipment independent description of the process, because is based on the experience of the processed materials, and so it remains valid throughout the entire development lifecycle.” Building on this foundation, project teams can variously identify and track scale-up risks, safety and environmental risks, resources consumed and the location and nature of process emission, and thus develop strategies by which they may be minimised and mitigated.

In ETERNAL Britest is building upon the PDD’s strength as a visual map of relevant process understanding by extending the scope of study to the entire product lifecycle from the upstream sourcing of raw materials and service utilities through the downstream use and disposal of products. The resulting output is dubbed (logically enough) a Supply Chain Definition Diagram (SCDD) and it opens up similar advantages to a PDD for improvement projects where the manufacturing process is only part of the picture.

“A clearly mapped supply or value chain can really help a team get to grips with not only where the impacts of their business arise but can act as a springboard for informed creativity in deciding how to do something about them in a cost-effective way,” says Rob Peeling. “We are also working in ETERNAL on a new project management tool to help technical managers identify and set improvement targets for impact reduction, and to track progress relative to them even when performance data is limited or subject to uncertainty.”

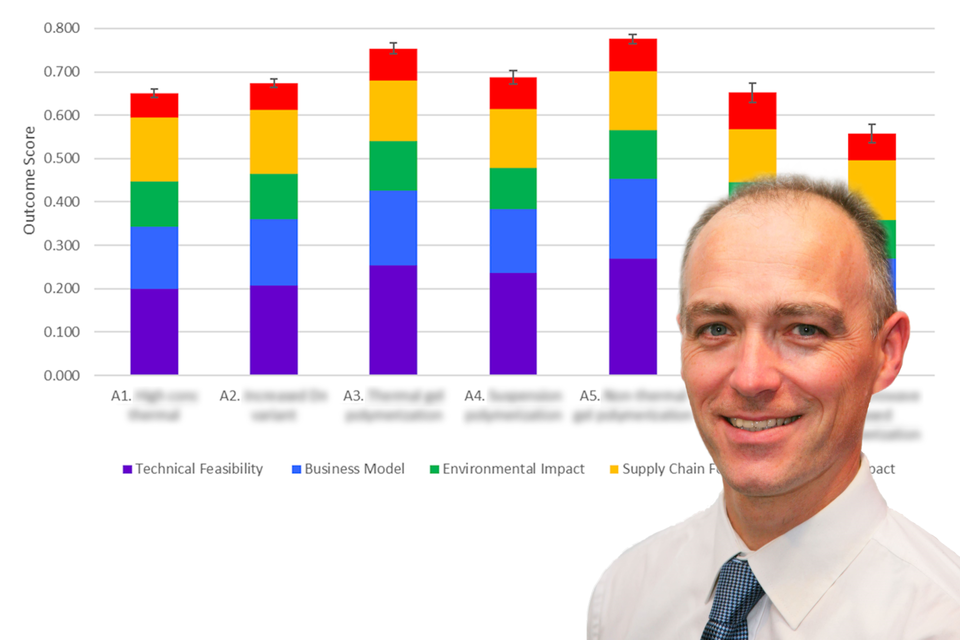

Uncertainty can also be a challenge when it comes to weighing up the complex interplay of multiple criteria which is often required when making strategically important decisions during an innovation project. Project teams frequently find themselves at a crossroads and facing a decision that could make or break the innovation. Examples might include deciding whether a continuous manufacturing process might confer advantages over a batchwise approach, or whether a decentralized manufacturing model would open up new supply flexibilities, or whether a bio-based rather than conventional synthetic strategy offered the best way forwards, but every situation is different.

According to Britest Technical Communications Specialist John Henderson, the challenge in perceiving the best way forwards is that, “You can’t just ask ‘Which is more sustainable, A, B or C?’” Indeed, even dividing that question into the classic environmental, economic and social ‘pillars’ of sustainability is a fairly superficial treatment of a deep question. Britest has taken on that challenge by developing a comprehensive framework for early-stage sustainability assessment (FESSA) which they are currently road-testing with some of the teams working on ETERNAL’s industrial case studies. The framework provides a two-level hierarchical structure for assessing relative sustainability amongst a set of alternatives from the earliest stages of process or product development. “Turning their assessment into numbers, we can readily harness multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) methods to help project teams cope with both the inherent complexity of the sustainability question and any uncertainty in their current knowledge to identify their ‘best bets’ for a sustainable innovation from the range of possible pathways they may be considering.”

As a knowledge-driven business committed to open innovation Britest plans to publish full details of their methodological developments during the ETERNAL project. Stay in touch to find out more.

1. Why 'bio' and 'green' don't mean what you think, Isabelle Gerretsen, BBC Future, 31st March 2022

3. The Green Consumer Paradox, Thomas Husson, Forrester Featured Blogs, 16th December 2021

This site uses cookies that enable us to make improvements, provide relevant content, and for analytics purposes. For more details, see our Cookie Policy. By clicking Accept, you consent to our use of cookies.